VSK TN

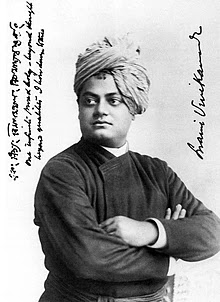

PEOPLE OF CHENGALPATTU RISKED THEIR LIVES TO HAVE A GLIMPSE OF SWAMI VIVEKANANDA

When Swami Vivekananda, after his successful return from the World Religious Conference at Chicago entered India through Kanyakumari. He traveled from Kanyakumari to Chennai by train. Since the train had to pass through Chengalpattu before reaching Chennai, and there was no official stop at Chengalpattu, the people gathered and requested the station master to stop the train at Chengalpattu station. When the request was denied, the people layed flat on the railway track and made the train stop. Swami Vivekananda delivered a speech for 10 minutes and the people were happy.

AN OLD WOMAN OF MADRAS WHO CONSIDERED SWAMI VIVEKANANDA AS THIRUGNANASAMBANDAR (SHAIVA SAINT)

6 Feb 1897

When the train bringing the hero-monk steamed into Egmore Station, Madras, on the morning of February 6, 1897, there were thundering shouts of applause. The enthusiasm shown was unprecedented in the history of Madras. An account of the Swami’s entrance into the city can be conveniently given in the words of one of the leading papers:

Due to previous information widely disseminated that Swami Vivekananda would arrive at Madras this morning by the South Indian Railway, the Hindus of Madras, of all ages and of all ranks, including young children in primary schools, grown-up students in colleges, merchants, pleaders and judges, people of all shades and varieties, and in some instances, even women, turned up to welcome the Swami on his return from his successful mission in the West. The railway station at Egmore, being the first place of landing in Madras, had been well fitted up by the Reception Committee who had organized the splendid reception in his honour. Admission to the platform was regulated by tickets rendered necessary by the limited space in the interior of the station; the whole platform was full. In this gathering all the familiar figures in Madras public life could be seen. The train steamed in at about 7.30 a.m., and as soon as it came to a standstill in front of the south platform, the crowds cheered lustily and clapped their hands, while a native band struck up a lively air. The members of the Reception Committee received the Swami on alighting. The Swami was accompanied by his Gurubhais [brother-monks], the Swamis Niranjanananda and Shivananda, and by his European disciple Mr. J. J. Goodwin. On being conducted to the dais, he was met by Captain and Mrs. J. H. Sevier, who had arrived on the previous day with Mr. and Mrs. T. G. Harrison, Buddhists from Colombo and admirers of the Swami. The procession then wended its way along the platform, towards the entrance, amidst deafening cheers and clapping of hands, the band leading. At the portico, introductions were made. The Swami was garlanded as the band struck up a beautiful tune. After conversing with those present for a few minutes, he entered a carriage and pair that was in waiting, accompanied by the Hon. Mr. Justice Subrahmanya Iyer and his Gurubhais, and drove off to Castle Kernan, the residence of Mr. Biligiri Iyengar, Attorney, where he will reside side during his stay in Madras. The Egmore Station was decorated with flags, Palm leaves and foliage plants, and red baize was spread on the platform. The “Way Out” gate had a triumphal arch with the words, “Welcome to the Swami Vivekananda”. Passing out of the compound, the crowds surged still denser and denser, and at every move, the carriage had to halt repeatedly to enable the people to make offerings to the Swami. In most instances the offerings were in the Hindu style, the presentation of fruits and cocoanuts, something in the nature of an offering to a god in a temple. There was a perpetual shower of flowers at every point on the route and under the “Welcome” arches which spanned the whole route of the procession from the station to the Ice-House, along the Napier Park, via Chintadripet, thence turning on the Mount Road opposite the Government House, wending thence along the Wallaja Road, the Chepauk and finally across the Pycrofts’ Road to the South Beach. During the progress of the procession along the route described, the receptions accorded to the Swami at the several places of halt were no less than royal ovations. The decorations and the inscriptions on the arches were expressive of the profoundest respect and esteem and the universal rejoicing of the local Hindu Community and also of their appreciation of his services to Hinduism. The Swami halted opposite the City Stables in an open pandal and there received addresses with the usual formalities of garlanding.

Speaking of the intense enthusiasm that characterized the reception, one must not omit to notice a humble contribution from a venerable-looking old lady, who pushed her way to the Swami’s carriage through the dense crowds, in order to see him, that she might thereby be enabled, according to her belief, to wash off her sins as she regarded him as an Incarnation of Sambandha Moorthy [a Shaiva saint of Tamil Nadu]. We make special mention of this to show with what feeling of piety and devotion His Holiness was received this morning, and, indeed, in Chintadripet and elsewhere, camphor offerings were made to him, and at the place where he is encamped, the ladies of the household received him with Arati, or the ceremony of waving lights, incense, and flowers as before an image of God. The procession had necessarily to be slow, very slow indeed, on account of the halts made to receive the offerings, and so the Swami did not arrive at Castle Kernan until half past nine, his carriage being in the meanwhile dragged by the students who unharnessed the horses at the turn to the Beach and pulled it with great enthusiasm.

THE SCHOOL TEACHER OF CHENNAI WHO SOLD HIS WIFE’S GOLD ORNAMENTS TO EXTEND FINANCIAL HELP TO SWAMI VIVEKANANDA

It was around 1890/91 that Alasinga Perumal, a school teacher learnt of the upcoming Parliament of World Religions from Yogi Parthasarathy Iyengar who, by virtue of his connections with the Hindu League of America and scholarly reputation, had been invited to participate. Representatives from various communities except the Hindu community had been named. Alasinga and his friends saw the Parliament as a good opportunity for the Hindus to present their faith to the world, but the question of who would travel to Chicago and represent Hinduism remained undecided even after days of discussion. The answer came with the arrival of Swami Vivekananda in Madras in early 1893.

Alasinga Perumal and his friends met Swami Vivekananda, who was then a guest of Manmathanath Bhattacharya, the first Indian Accountant-General of Madras, at his residence in San Thomé. Swamiji was introduced to the Madras public at the Triplicane Literary Society, where Alasinga was an active member. It was a place the Swamji was to later frequent and deliver many lectures. Swamiji was impressed by Alasinga Perumal, who shared his ideas and concerns about the motherland. Alasinga thus became a close confidant and disciple of Swami Vivekananda. Alasinga felt that Swami Vivekananda should be sent to Chicago as the representative of Hindus. When the idea was put to him, Swami Vivekananda readily agreed, having earlier been requested by the Maharaja of Mysore, the Raja of Ramnad and others to travel to the West and propagate the ideals of Hinduism. A subscription committee was formed under the leadership of Alasinga to raise funds, which did not always come easily. Alasinga even had to resort to door to door begging at times to raise the money. Soon, the princely sum of Rs.500 was collected. However, this sum was returned to the donors as Swami Vivekananda had second thoughts about his participation in the Parliament, when he took it as a bad omen that the Raja of Ramnad had failed to make the contribution promised by him for the purpose. Alasinga was disheartened that his efforts had gone waste.

However, much to Alasinga’s joy, the whole idea was revived, as Swami Vivekananda, encouraged by the reception accorded from the people of Hyderabad during his visit there, showed renewed interest in going ahead with the trip. The Nizam too offered a sum of Rs.1000 towards meeting the costs. Swamiji also had a vision of his Guru, Sri Ramakrishna, which he took as a divine command to make the journey.

Alasinga then renewed his efforts to collect subscriptions and, soon, nearly Rs.4000 was collected. He spared no efforts for the cause, even going as far as Mysore to meet the Maharaja and getting contributions from him. Swami Vivekananda sailed to Boston from Bombay, where Alasinga saw him off. Throughout his stay in America, Swami Vivekananda wrote letters to Alasinga and his other close disciples, keeping them informal of his activities. When he once wrote that he was running short of funds, Alasinga immediately borrowed Rs.1000 from a merchant which, along with his monthly salary and money raised from selling his wife’s gold ornaments, he sent by cable immediately.

In 1894, Alasinga started the Young Men’s Hindu Association. His literary contribution started the next year, when, at the behest of Swami Vivekananda, he launched Brahmavadin, a journal dedicated to Hindu religion and philosophy. Assisting him in his efforts were fellow disciples of Swami Vivekananda like Dr. M.C. Nanjunda Row and Venkataranga Rao. The first issue came out in September 1895 from the Brahmavadin Press, which had been set up in Broadway. Swami Vivekananda himself contributed articles regularly to the journal and also helped get overseas subscribers. The Brahmavadin Publishing Company was also established by Alasinga, through which he edited and published titles under the ‘Brahmavadin Series’. In July 1896, Alasinga was instrumental in starting the Prabuddha Bharata, or Awakened India, a journal that has been in uninterrupted publication ever since, making it the oldest magazine of its kind in the country.

Alasinga was actively involved in the various celebrations and meetings that were held across the city during the nine-day stay of Swami Vivekananda on his return from the West. He also played an active role in the early years of the Madras Mutt that was established by Swami Ramakrishnananda in 1897.

The death of Swami Vivekananda (July 1902) and the passing away of his wife (in 1905) were setbacks that only made heavier the toll on his health that years of selfless public work and service had taken. He passed away on May 11, 1909, when he was just 44 years.

The high regard Swami Vivekananda had on Alasinga Perumal can be gauged from his own words: “One rarely finds a man like our Alasinga in this world, one so unselfish, so hard-working, and devoted to his guru, and such an obedient disciple is indeed very rare on earth. His devotion I can never repay”